Jane

Preston’s 2015 documentary on Paul Gascoigne clearly demonstrates one thing at

least - the grim reality behind the epigram of that Greek philosopher

Heraclitus, on your character being your destiny. So in contrast to the clean-cut,

eloquent and always impeccably behaved Gary Lineker, who was famously never

booked in his playing career and who went on to carve out a successful

broadcasting career after hanging up his football boots, Paul Gascoigne’s playing

career was marked by a few heady highs that demonstrated extraordinary levels

of footballing potential and then lots of lows, many of them self-inflicted, both on and off

the field.

Heraclitus (535 - 475 BC), Greek philosopher and a man who predicted a challenging life for Paul Gascoigne, two and a half millennia before he was even born

Most of Preston's documentary is based on a lengthy interview with

Gascoigne himself, with some very supportive pro-Gascoigne opinions and

soundbites thrown in by Jose Mourinho, Wayne Rooney and, most of all, by the

ever polite and genial Gary Lineker.

As

someone who never supported any of the teams that Gascoigne played for, my

knowledge of and interest in him during his playing career in the 1980s and

1990s was somewhat limited and probably dominated by his reputation for

partying and play acting. So I went to this documentary (partly driven by the COVID-19

lack of sport spectating options) to see what the story really was with

Gascoigne.

Unfortunately, Preston’s documentary provides very little new or revealing

information on Gascoigne. And instead of a balanced and in depth analysis, we get a

superficially polished hagiography. In fact, the almost condescending levels of

kindness to Gascoigne combined with the willful blindness to his many deeply

frustrating faults and failings means that this documentary ultimately does

Gascoigne a disservice.

So even

though I could never claim to have had a great knowledge of Gascoigne’s playing

career or personal life, I learned very little new information from this documentary and

instead came away with a sense that it was some kind of propaganda piece designed to help

restore his image and rose-tint the memories of this once ‘national treasure’

(yes: that awful term is used to describe him at one stage in this

documentary).

Gascoigne's footballing story (and a little bit about his life)

Gascoigne's footballing story (and a little bit about his life)

The

documentary takes us on a chronologically straightforward biographical journey

from Gascoigne’s childhood, growing up in late 1960s and 1970s poverty in

Gateshead, just a few miles from Newcastle United’s home ground of St. James’s

Park and from where he could hear the crowds cheering in the Gallowgate End on

a Saturday afternoon, through to his early footballing years with Redheugh Boys

Club and then on to his signing with Newcastle United at the age of sixteen. We

get a few insights into those early years, but nothing earth shattering. He

played football in the streets with friends and sometimes on his own, starting

with a tennis ball until his father bought him his first leather football at

the age of seven. There is no doubt that he loved football and he was not

easily parted from that leather ball.

A boyish Gascoigne

Apart from the standard 'jumpers for goalposts' stories, Gascoigne also recounts a terrible early tragedy during this time, when the younger brother of a friend of

his was hit by a car and killed. Gascoigne was ten at the time and the accident

happened after they had run out of a shop. Gascoigne felt awful guilt as a

result and he recalled that after the funeral he spent three days in the room

where the boy’s coffin had been kept, before going on to develop what sound

like involuntary tics and facial grimaces, possibly as a psychological reaction

to the trauma. He had some brief psychiatric input at that stage.

His

apprenticeship years with Newcastle United were happy and productive, but he

was already getting some attention for being a somewhat unconventional athlete,

being described by one commentator as looking like ‘he plays for your local

Sunday pub team…wearing T-shirt, anorak, jeans…and a diet of Mars bars and

brown ale’. He had tough treatment from

hard managerial men such as Arthur Cox and Jack Charlton, but nothing out of

the ordinary for the times. And

he seemed to enjoy every minute of this phase of his career.

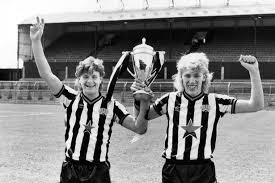

With Joe Allon and the 1985 FA Youth Cup in his early days at Newcastle United

Clips from those early days show a

strong and agile player.

He used his upper body strength and arms to 'protect' himself and through his

football he seemed to enjoy expressing his own personality and style, in a way

that was and still is quite unusual for English footballers. There was ‘a lack

of fear in his game’ and he was undoubtedly a show off, as are so are many great

players in their early days at least.

There’s

a brief review of his clash with Vinnie Jones of Wimbledon in 1988 which began

with Jones screaming at Gascoigne in the tunnel at the start of the match: ‘Me and you, fat

boy: I can’t play football and neither can you today’. The clash of Gascoigne’s

skill against the brute bullying force of Jones culminated in one of the most

infamous football images of all time.

Vinnie Jones 'marking' Gascoigne, Plough Lane, 1988

Jones and Gascoigne doing a reenactment of the 1988 incident

Soon

after this, Gascoigne was off to Spurs, after turning down the (as yet

relatively unsuccessful) Alex Ferguson of Manchester United. It seems that

Gascoigne was swayed in his decision by Spurs’ promise of a house and car for

his parents and a sun-bed for one of his sisters. In an act of typical Fergusonian bitterness, he refused to talk to Gascoigne for six years after the rejection. But we are left to wonder if Gascoigne might have prospered professionally and personally had he gone to work under

the grumpy disciplinarian at Manchester United as opposed to the comparably warmer and cosier character of Terry Venables at Spurs. It would have been a useful question

to put to Gascoigne in this documentary.

His

years at Spurs were marked by some of his greatest achievements and some of his biggest

mistakes. During this time, he got his start for England, reaching the

semi-final stage of the World Cup in Italy in 1990, England's loftiest level of progression since 1966. In the semi-final, he

picked up his second yellow card of the tournament, for a rash challenge on the German Thomas Berthold, thus famously crying copious amounts during and directly after

the match, realizing that he would be unable to play in the World Cup Final

should England advance. Whether it was genuine puzzlement or a faux innocence, Gascoigne

professed not being able to understand Berthold's writhing and screaming after he had fouled him, saying that ‘When I get kicked I take it as a

compliment’, thus implying that he should perhaps have been thanked by the

German for administering such a crushing tribute.

It was decided by England manager Bobby Robson

and Gascoigne that he ‘didn’t feel right to take a penalty’ in the ensuing

shootout at the end of that German semi-final, and England lost 4-3, thus starting a long sequence of penalty

shoot-out heart-breaks that only came to an end at the 2018 World Cup against

Columbia. Gary Lineker, in reflecting on Gascoigne’s non-participation in the 1990

shoot-out says he ‘wishes he had’ taken a penalty and again one wonders what other teammates

would have thought of Gascoigne’s overwhelming self-pity and tears on the day and his lack of

participation in the shootout.

Tears in Turin - World Cup 1990

Back in England, he won a much coveted (at that time at least) FA Cup winner’s medal with Spurs in

1991, after knocking out arch rivals Arsenal in the semi-final and scoring a 30

yard pile-driver free kick in the process. This was one of his most special footballing moments so it warrants a video link:

Thwack!

A brief clip from a post-match interview, with Gascoigne's adrenaline still in full flow, shows him at his very boyish best, when he tells a reporter: ‘I’m now away to get my suit measured’ (for the FA Cup Final).

And then things took a turn for the worst. Despite helping Spurs to that 1991 FA Cup Final with his wonderful free kick, he was stretchered off early in the first half because of a wild kick/tackle on Gary Charles of Nottingham Forest that resulted in Gascoigne rupturing the cruciate ligament of his right knee and putting himself out of the game for eight months, thus delaying his planned transfer to Italian club Lazio in the summer. His Spurs teammates brought the FA Cup to him in is hospital bed.

There

are three interesting snippets from this documentary, new to me, that come from these two years. The

first is purely footballing. As Gascoigne placed the ball on the ground for

that FA Cup semi-final free kick against Arsenal, Gary Lineker ran purposefully

towards him and said ‘Have a go’. Gascoigne may already have had the idea in

mind or he may have taken Lineker’s advice. Either way, the ball ended up in the

top corner of the Arsenal goal, and it serves as a perfect example of his fleeting brilliance and perhaps too the wisdom of the technically less gifted Lineker.

A

year earlier, Lineker also imparted some advice to Gascoigne that was (to

Gascoigne at the time at least) somewhat obtuse and lost on him. As the England team plane

arrived home after their World Cup journey in Italy, Lineker said to him, sensing the media

frenzy and hype that was about to envelop Gascoigne: ‘Paul – be

careful’.

The

third interesting snippet is from soon after arriving back from that World Cup when

Gascoigne was interviewed on television by Limerick’s own Terry Wogan. Wogan

outlined in his usual avuncular tone to a grinning Gascoigne how he was living every young man’s dream

right now but, with a cautionary tone, he added prohpetically that ‘it could turn out to be

a nightmare’.

As

with the turning down of Manchester United, one has to wonder if Gascoigne

might have had an easier journey had he listened more carefully to both Lineker

and Wogan.

Gary Lineker notices Gascoigne's tears in Turin. Gascoigne's Spurs and England teammate always seemed to have an inkling as to his vulnerability

Terry Wogan demonstrated Heraclitean levels of wisdom

when he hinted at potential for a future 'nightmare' for Gascoigne

Dotted

in among the football sequences are brief examples of Gascoigne’s playfulness that sometimes went a little over the top,

e.g his taking an ostrich to a training session to shock his team-mates or his

asking Princess Diana for a kiss as she met the teams before the FA Cup final

and, when she shyly refused, cheekily kissing her hand.

Stealing a kiss from Princess Diana at the FA Cup Final, 1991

After

Spurs and recovering from his cruciate injury, Gascoigne went on to play for Lazio in the then furnace of Italian football,

scoring a rare headed goal in front of 105,000 spectators in the Rome derby

against Roma. At Lazio he sustained another significant knee injury, this time

in training and resulting again in a further sustained period out of the game.

Gascoigne then left Lazio in a club record (4.3 million pounds) signing for Glasgow Rangers and enjoyed his most

successful time as a player, in terms of silverware at least, winning two league

titles, a Scottish Cup and League Cup. It was also during this period that he

scored his most famous goal for England, against Scotland in the Euro 96

championships. The goal itself was sublime in its execution, so I have included a video link below. It was also tinged with extra significance because he was earning his living in Scotland at the time.

Gascoigne fires home against Scotland at Euro '96

And the famous 'dentist's chair' celebration after the goal

And here's a video link to the goal - well worth a watch

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=evnXFu744uY

The ‘dentist’s chair’ celebration after that genius goal tells the other side

of Gascoigne. The celebration was Gascoigne's and the England team’s way of having a go back at

the media, who had outed their partying before the championships,

with Gascoigne and other team members being administered shots in a bar while lying back

in a 'dentist’s chair'.

Another standout moment during the Rangers years was his goal celebration where he mimicked playing a flute (as in an Orange parade), thus attracting the ire of an Irish republican who sent him death threats that were verified by the police as being serious and which were not lifted for six months. Gascoigne’s poor judgement for this choice of goal celebration was only compounded by his apparent disbelief that it could have caused offense.

After Rangers, he had brief spells with Middlesbrough, Everton, Burnley, Chinese club Gansu Tianma and Boston United, before retiring in 2004.

The documentary - not enough warts

Another standout moment during the Rangers years was his goal celebration where he mimicked playing a flute (as in an Orange parade), thus attracting the ire of an Irish republican who sent him death threats that were verified by the police as being serious and which were not lifted for six months. Gascoigne’s poor judgement for this choice of goal celebration was only compounded by his apparent disbelief that it could have caused offense.

After Rangers, he had brief spells with Middlesbrough, Everton, Burnley, Chinese club Gansu Tianma and Boston United, before retiring in 2004.

The documentary - not enough warts

This documentary is either very sparing or completely lacking on some key issues.

Gascoigne’s alcohol and drug use is mentioned almost in passing and in a ‘nod

and wink’, ‘boys will be boys’ kind of way. There is absolutely no mention of

Gascoigne’s relationships, his marriage or his daughter. And although he

frequently hit the headlines in the 1990s as Gascoigne’s partying sidekick,

there is no mention of Jimmy 'Five Bellies' Gardner. Very little is revealed in terms of Gascoigne's family of origin, apart from early allusions to poverty and, much later, his

sister ‘sectioning’ him to a psychiatric hospital because of increasing

paranoia and chaotic behaviour. He mentions being ‘close to death’ on two

occasions but, frustratingly, no further detail is elicited or provided.

And

then it all ends up rather neatly. Gascoigne’s paranoia (most probably not helped by prolonged and heavy alcohol and drug use) is almost excused as being reasonable and

vindicated because of the hacking of his phone by journalists for 11 years up to 2005. At

best, this is an oversimplification of those years of his life, although he was undoubtedly treated very badly by certain journalists.

To

add to the frustration of watching this documentary, the contributions of Jose Mourinho and Wayne Rooney are trite, glib and delivered with a lack of real

conviction. Rooney in particular is underwhelming in his comments. His main

contribution is to say, at least three or four times, that Gascoigne was ‘the

greatest player that England ever had’. The irony is that, even just among the three England players featured in this documentary, Gascoigne's contribution to his country comes in a distant third. And regarding the performance statistics for his particular position, he is not even close to being England's best midfielder, let alone 'the greatest player that England ever had'. The average England caps of Bobby Charlton, Steven Gerrard, Frank Lampard and Paul Scholes are 98 and their England goals average is 28. Gascoigne's England caps are 57, with just 10 goals. No amount of cheeky smiles and fancy turns can cover up these stats and one has to wonder if Wayne Rooney was having an off day in terms of his knowledge of English football history when this documentary was being made.

Despite the obvious shortcomings of the documentary, however, there is no doubt that Gascoigne's likeability and boyish innocence comes shining through.

And although too few in retrospect, his most memorable exploits on the football field mean that he is destined to go down as one who could have been one of England's greats.

Despite the obvious shortcomings of the documentary, however, there is no doubt that Gascoigne's likeability and boyish innocence comes shining through.

And although too few in retrospect, his most memorable exploits on the football field mean that he is destined to go down as one who could have been one of England's greats.

No comments:

Post a Comment