Olympian warfare

George Orwell’s view that

sport was ‘war minus the shooting’ has been borne out by countless examples,

most dramatically at major international sporting events such as the Olympics.

The United States and sixty four other countries boycotted the 1980 Moscow

Olympics completely, in protest at the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan and as a

general symptom of Cold War politics. Four years later, The USSR led thirteen

Eastern Bloc and affiliated Communist nations in a retaliatory boycott of the

Los Angeles Olympics. There are also many examples of bilateral collisions during

Olympic games between nations with intense rivalries, such as the three hockey finals contested

between Pakistan and India in 1956, 1960 and 1964 and the controversial

basketball final of 1972, between the United States and the USSR.

And if Orwell was right and

sport is a kind of tame warfare, then your country's medal count is a proxy

measure for where you’re at in the international pecking order. Scanning over

the table for Olympic medals won, there are vast levels of disparity between

the top dogs such as the United States (2,827 medals), Great Britain (883

medals) and France (840 medals) in comparison to nations such as Paraguay and

Jordan, with only one medal each. In fact, such has been the dominance of the

United States that they have won 15% of all medals since the first modern

games in 1896.

However, interpreting the

medals table is not as simple as it might seem. The 124 years of Olympic games

has seen multiple changes in national borders, with many countries disappearing and new countries appearing at different stages and in different forms. It gets

particularly complicated when you look at countries such as Russia and Germany,

as they have both had Olympic Games representatives under the guise of several

different national flags, e.g. German athletes have represented East Germany,

West Germany, Saarland and Germany, while Russian athletes have represented the

Russian Empire, the USSR and Russia. When all the different German guises are

combined, their medals total is 1,754 while the Russian haul is 1,910.

Then it gets even more

complicated when you consider the relative populations of different nations.

When calculations are done for medals won per population, Finland (55 medals

per million population) comes out on top. This gives Finland fifteen times more medals than Ireland, with a population only slightly larger

than ours. But then to complicate things further, countries such as Finland

compete at both winter and summer Olympics, thus increasing their medal chances

considerably.

And I won't even get into the complexities of 'weighting' the gold, silver and bronze medals in terms of their relative value.

Ireland’s

Olympic medals

So where does all this leave

Ireland? The answer is, in short, not too bad. It is pleasing to see that

our 31 medals outranks those of European neighbours Portugal (24 medals) and

even Nigeria (25 medals), a country with a population 40 times bigger than ours

(although they have competed as a nation at 5 less Olympics than Ireland).

However, when we look at countries of similar population, similar wealth and

with a similar number of Olympics appearances as Ireland, the picture is not so

positive. And I’m talking specifically about the overachieving New Zealand here, with their 120

medals.

So for Ireland, every

Olympic medal we can squeeze out is precious. And while we are a long way behind the Kiwis, just two more medals

would push us up the medals table above Indonesia (with a population 55 times that of ours).

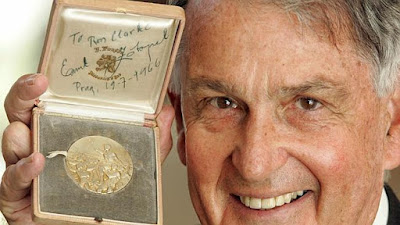

Going through the history books reveals a lot of precious medals won by Irish athletes that are assigned to other nations. For example, the Great Britain (England) team beat the Great Britain (Ireland) team in the 1908 hockey final – that’s a silver medal we don’t get credit for. And there’s the gold medal in tennis won by John Boland in Athens in 1896, again credited to Great Britain. And there’s Peter O’Connor, with gold and silver at the 1906 games, again credited to Great Britain, despite his dramatic and passionate protests, climbing a flagpole at the medals ceremony to unfurl 'the old flag of Erin'.

Going through the history books reveals a lot of precious medals won by Irish athletes that are assigned to other nations. For example, the Great Britain (England) team beat the Great Britain (Ireland) team in the 1908 hockey final – that’s a silver medal we don’t get credit for. And there’s the gold medal in tennis won by John Boland in Athens in 1896, again credited to Great Britain. And there’s Peter O’Connor, with gold and silver at the 1906 games, again credited to Great Britain, despite his dramatic and passionate protests, climbing a flagpole at the medals ceremony to unfurl 'the old flag of Erin'.

An example of 'the old flag of Erin', heroically hoisted at the 1906 Olympics by double medal winner Peter O'Connor

But we can’t blame

everything on the British. A review of the official record of Irish Olympic medals includes

16 won in boxing, 7 in athletics, 4 in swimming, 2 in sailing, 1 in rowing and

1 in equestrian. However, there are a further three precious medals won by

Irish competitors, competing under the Irish flag, that seem to have slipped

from memory.

Following the old maxim of

‘mens sane in corpore sano’, Baron de Coubertin was keen that art competitions

be included in the Olympics and that was the case from 1912 to 1948, with the

competing entries required to have a sporting theme. And here’s where our three

missing Irish medals come in.

Oliver St. John Gogarty

(1878 - 1957), doctor, writer and forever immortalized by James Joyce as the inspiration for Buck

Mulligan in Ulysses, won a bronze medal in the 1924 Paris Olympics in the

Literature competition for his ‘Ode to the Tailteann Games’.

Oliver St. John Gogarty (1878 - 1957)

Letitia Hamilton (1878 - 1964), landscape artist, also won a bronze medal (London Olympics, 1948), in the category of painting

and graphic art (oils and water colours) for her painting ‘Meath Hunt

Point-to-Point Races’.

The Meath Hunt Point-to-Point Races,

by Letitia Hamilton (1878 - 1964)

by Letitia Hamilton (1878 - 1964)

And the third medal winner is a

special one for me as it happens to be probably my favourite painting by my favourite

artist and, until I started to do some background reading for this blog, I hadn't realized that it was also an Olympic medal winner.

Confusingly listed in some places as ‘Natation’ (because it was entered in the

1924 Paris Olympics), the raw Dublin vibrancy of ‘The Liffey Swim’ by Jack B.

Yeats won him a silver medal for Ireland.

'The Liffey Swim' by Jack B. Yeats (1871 - 1957)

And then - Tipperary

hurling

Finally, another Olympian

artistic entry also has a very special place in my heart, and that is Limerick

artist Sean Keating’s evocative ‘The Tipperary Hurler’ that was entered for the

1928 Amsterdam Olympics. Keating produced a range of works that proudly

displayed the confidence and special cultural qualities of the newly independent Ireland

in the 1920s and this painting was based on

a composite of legendary Tipperary hurler John-Joe Hayes and Ben O’Hickey (an

IRA member and art student, from Bansha).

So while the great and ancient game of

hurling remains primarily a passion for the Irish and our diaspora and has not as

yet achieved Olympic status (wouldn't that be an easy gold medal for us), hurling

did make a brief appearance at one Olympics, embodied (of course) by a Tipp

man.

The Tipperary Hurler, by Sean Keating