Emil Zátopek: a brief history

Emil

Zátopek always had it tough in every respect, from the

very beginning until the very end. Born in 1922 into extreme poverty, the

seventh of eight children, he lived through the cruel Nazi occupation of his Czech

homeland, followed by decades spent enduring the tyrannical and paranoid Soviet

backed Communist regime that only finally came to an end a few years before his

death in the year 2000, following a number of increasingly disabling strokes.

Added to the stifling and potentially spirit-crushing geopolitical environment of his lifetime, his parents initially discouraged him from running and, based on reviews of videos and contemporary accounts of his unconventional and tortured running style, he was probably not a naturally talented athlete. And he never had a coach.

But it was his smiling acceptance of the toughness and challenges in his life that made him a legend.

Added to the stifling and potentially spirit-crushing geopolitical environment of his lifetime, his parents initially discouraged him from running and, based on reviews of videos and contemporary accounts of his unconventional and tortured running style, he was probably not a naturally talented athlete. And he never had a coach.

But it was his smiling acceptance of the toughness and challenges in his life that made him a legend.

Emil Zátopek with that characteristic pained look

Richard Askwith's wonderful biography - providing the inspiration and most of the source material for this blog

And not only did

he manage to survive through tumultuous and dangerous times but, training alone

at gut wrenching intensity levels never seen before, he became the greatest

runner of his generation, if not all time. His novel training methods became legendary in themselves, e.g. those flat-out 400m sprints up to 100 times a day or running in heavy army kit and boots through the forests near his home, sometimes in snow.

At the height of his powers, he was as famous and adored as Usain Bolt and Lionel Messi are now. And little hints of his fame were evident long after his retirement from running. His biographer Richard Askwith tells the story of Emil visiting Finland in his twilight years, to meet some old running friends. He asked a local for directions, speaking in his self-taught Finnish. When the local asked him where he had come from and Emil told him, the local, not recognizing the old man before him, said ‘Ah, the land of Zátopek’, to which Emil replied ‘I am Zátopek’ and broke down in tears.

At the height of his powers, he was as famous and adored as Usain Bolt and Lionel Messi are now. And little hints of his fame were evident long after his retirement from running. His biographer Richard Askwith tells the story of Emil visiting Finland in his twilight years, to meet some old running friends. He asked a local for directions, speaking in his self-taught Finnish. When the local asked him where he had come from and Emil told him, the local, not recognizing the old man before him, said ‘Ah, the land of Zátopek’, to which Emil replied ‘I am Zátopek’ and broke down in tears.

Following a gold

(10,000 metres) and silver (5,000 metres) at the first post war Olympics in

London in 1948, he won an unprecedented three gold medals (5,000m, 10,000m and

the marathon, his first race at that distance) at the Helsinki Olympics in 1952

while his wife Dana also won gold, in the javelin. I have also alluded to these

events in two earlier blogs:

https://sportyman2020.blogspot.com/2020/03/memories-of-helsinki.html

https://sportyman2020.blogspot.com/2020/03/emil-and-dana-olympian-love-affair.html

https://sportyman2020.blogspot.com/2020/03/memories-of-helsinki.html

https://sportyman2020.blogspot.com/2020/03/emil-and-dana-olympian-love-affair.html

Throughout his career, he won countless track

and cross-country races at distances from 1,500 metres upwards, over a ten year

period of absolute dominance. Along with his medals and awards, he set eighteen

world records in the process.

Emil and Dana

When he fell out

of favour with the Communist regime because of, among other things, his role as

a brave supporter of the Prague Spring movement in 1968, he was dismissed from

the army and went on to spend several years in enforced work in squalid conditions as an itinerant

manual labourer with only limited contact allowed with his beloved Dana.

Emil addressing the crowds during the Prague Spring of 1968

As a soldier himself, Emil tried to communicate with the Russians and other Eastern Bloc soldiers when their tanks rolled in to Prague in August 1968 to crush the popular uprising against an increasingly restrictive Communist regime

But despite all the

hardship he endured and his multiple glittering achievements, it is his warmth,

humour and love of people that comes through most in Richard Askwith’s

biography. During his running career, Emil made lifelong friends from all over

a bitterly divided Cold War world. His natural charm and interest in others

meant that he was able to reach across political and ideological divides and

connect with the humanity in all of his competitors. His self-taught ability to

converse in at least eight languages was an indication of his interest in and

respect for people from vastly different cultures and backgrounds.

With his great friend and rival Alain Mimoun of France, who said on his passing: 'I am losing a brother, not an adversary. It was fate that brought me together with such a gentleman'.

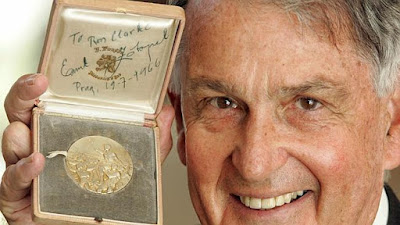

Australian runner Ron Clarke with a surprise gift from his friend Emil Zátopek: 'I do know that no one cherishes any gift more than I do, my only Olympic gold medal, and not because of what it is but because of the man whose spirit it represents'.

Of course there

are also many unanswerable questions about his life, especially considering the

dark and troubled times in which he lived. As an officer in the Czechoslovak

army during the Cold War, his athletic prowess was utilized by the ruling

Communist elite and propagandists. And darker questions have been raised about

him being a spy or informer. The latter issue has been addressed by Richard Askwith and his conclusion, based on multiple interviews

with contemporaries and reviews of previously secret government documents, is

that Emil was if anything ‘a person of interest’ (i.e. himself under suspicion)

and, at most, passively compliant with a brutal and all powerful regime.

Some lessons from Emil

Zátopek

Our current

radical restrictions in business, sporting activities and all aspects of social

behaviour that have been invoked to help combat the global COVID-19 pandemic

have caused abrupt changes in our lifestyle that have never been seen in most

people’s living memory. Now heading into the third week of such restrictions in

Ireland and with tighter restrictions in place from midnight last night,

people are trying to make the most of their newly limited lifestyles while also keeping themselves and their families safe.

Like many involved in running and outdoor pursuits generally, until yesterday it was a relief for me know that it was still permissible to have unlimited exercise outdoors, while bearing in mind the necessity of social distancing from others. And because of the mentally and physically restricting nature of our recent societal changes, running and other outdoor activities have had something of a boom in recent weeks, as could be seen anecdotally in towns and villages in Ireland and also recently noted in New York. However, from midnight last night, outdoor exercising is limited to brief periods only, and only within 2 kilometres of one's home.

Like many involved in running and outdoor pursuits generally, until yesterday it was a relief for me know that it was still permissible to have unlimited exercise outdoors, while bearing in mind the necessity of social distancing from others. And because of the mentally and physically restricting nature of our recent societal changes, running and other outdoor activities have had something of a boom in recent weeks, as could be seen anecdotally in towns and villages in Ireland and also recently noted in New York. However, from midnight last night, outdoor exercising is limited to brief periods only, and only within 2 kilometres of one's home.

And although our

current societal restrictions are a tiny drop in the ocean of decades-long societal restrictions

endured by Emil Zátopek, it is tempting to draw a few parallels right now,

especially as he is on my mind so much having recently read his biography.

Emil Zátopek was

not unscrupulous or calculating enough to collude with and profit from

association with the ruling Communists or, earlier in his life, the Nazis. One

of my theories about him is that he realized that by excelling in running he

could escape the shackles of his military and political masters, briefly at least. And I believe this

explains why he always seemed so joyful when he attended the

Olympics or other major competitions, where he reveled in meeting with competing athletes from all over the world. These competitions

were brief periods of freedom and escapism away from the repressive regime of

his homeland, just as running or other outdoor pursuits (albeit in limited terms from today) during this global pandemic gives us very welcome respite

from worry and boredom.

So I set out for a run this morning that was within the new government restrictions, asking myself what Emil Zátopek would do in such a situation. And I just made the very most of it, as he would have done, seeing it as a brief mental and physical break. As a result I found that, instead of feeling like just another Saturday morning run, it took on the feeling of a guilty pleasure. I kept within two kilometres of home at all times, doing loops of local roads until I hit 10 km on my watch. And mindful of keeping the session brief, I ran at a faster pace than my usual 5 min/km for the 'long slow' Saturday morning run. As a result, the session was intense (although not at Zátopek levels of intensity) and especially satisfying and, forced to run on a different route than usual, I saw Ballina, Killaloe and the Shannon from some novel angles. And the locked down eeriness and lovely Spring sunshine added to the novelty, while seeing a few other runners and walkers out gave me a great sense of solidarity in our shared freedom.

So I set out for a run this morning that was within the new government restrictions, asking myself what Emil Zátopek would do in such a situation. And I just made the very most of it, as he would have done, seeing it as a brief mental and physical break. As a result I found that, instead of feeling like just another Saturday morning run, it took on the feeling of a guilty pleasure. I kept within two kilometres of home at all times, doing loops of local roads until I hit 10 km on my watch. And mindful of keeping the session brief, I ran at a faster pace than my usual 5 min/km for the 'long slow' Saturday morning run. As a result, the session was intense (although not at Zátopek levels of intensity) and especially satisfying and, forced to run on a different route than usual, I saw Ballina, Killaloe and the Shannon from some novel angles. And the locked down eeriness and lovely Spring sunshine added to the novelty, while seeing a few other runners and walkers out gave me a great sense of solidarity in our shared freedom.

Some final words

When

reading the biographies of great athletes, it is always tempting to pluck out

some inspirational quote from them that neatly sums up their attitude to

training, competing and to life in general. And Emil Zátopek, being such a warm,

garrulous and extroverted individual, had plenty of wise words and reflections

to impart. Summing up his views on hardship and endurance, he said: ‘It's at the borders of pain and suffering

that the men are separated from the boys’. Reflecting his warmer side, he

said: ‘Great is the victory, but the friendship of all is greater’. Regarding his famously tortured demeanour while running, he said 'I was not talented enough to run and smile at the same time'. And the

list of quotations, anecdotes and parables from his life

could go on and on.

However,

I will leave the last words here to Alžbeta Vlasáková, a Slovakian former farm-worker who

remembers Emil at perhaps the lowest point in his life, after his dismissal

from the army and when he was living in exile, doing hard manual

labour drilling wells throughout the countryside, and with military and government agents watching his every move:

‘He

used to run to Becov Bečov or

Mnichov, just by himself, on the roads. He wasn’t racing then. But he kept

running - because if you’re running, you’re alive’.

His finest moment: Emil entering the Olympic Stadium in Helsinki to win the marathon and pick up his third gold medal of the 1952 Helsinki Olympics

Good blog, thanks! I knew of his role in the Pragus Spring of '66 but did not know of his later internal exile and hard labour.

ReplyDeleteThanks Dermot. Yes he had a terrible time after the Prague Spring and more or less disappeared from public life for several years. He travelled the countryside with a small group of co-workers, drilling for water and digging ditches. They worked, lived and slept together for weeks on end. And the traditional caravan in which they all slept was known as a (here's a new word for you) maringotka!

ReplyDeleteGreat review Henry, looking forward to reading the book even more now.

ReplyDeleteThanks Declan! It's an excellent biography, and the author Richard Askwith is full of compassion for Zatopek's impossible situation in Communist Czechoslovakia. And the descriptions of Zatopek's training will pop into your mind and inspire you whenever you're flagging in the hills! Here's another recent article by Askwith on the Olympics - you might find it interesting:

Deletehttps://unherd.com/2020/04/how-the-olympics-could-rekindle-their-flame/

Henry